Dear comrades-in-arms, climate justice allies, and codeROOD sympathisers,

This is a farewell from codeROOD. After five active years dedicated to building the climate justice movement and two years of declining energy and loss of purpose, our grassroots collective has decided to compost itself.

We don’t believe continuity is the only measure of success. We have never prioritised becoming an institution that clings to perpetuating itself. Our goal was to stay dynamic and adaptable, instead of becoming a stagnant organisation. Some groups fizzle out discreetly, while others over well-publicised infighting. We have chosen to disband with nothing but care and kindness for each other.

We will keep our memories and carry our learnings forward. We hope to provide nutrients for new initiatives to sprout in the fertile soil where a diverse ecology of movements flourishes. We would like to take a moment to reflect on our intentions and experiences. We hope that the climate movement as a whole can benefit from our shared journey, as the struggle continues.

Let it be known that ordinary people can band together to do extraordinary things.

Origins.

The European climate justice movement emerged from the counter-globalisation mobilisations and converged around the COP15 Copenhagen summit in 2009. In the Netherlands, the eco-anarchist group GroenFront! inspired by EarthFirst! was the only grassroots environmental organisation to the left of the NGOs. They launched the Wij Stoppen Steenkool campaign in 2010 to target coal infrastructure in the Netherlands. This was the first step towards a mass, diverse movement that embraced disruptive and civil disobedient tactics. Their groundwork enabled new initiatives like ours to take root.

Some of us experimented with similar principles by organising Climate Games: a disobedient and playful action-adventure campaign where community building meets diversity of tactics. We targeted the Hemweg coal power plant (now decommissioned), then spread to the entire industrial port of Amsterdam (now supposedly “in transition”). We strengthened ties with food sovereignty activists at ASEED (who organised the Ground Control camp), and adapted the format for the COP21 Paris climate summit in 2015.

2015 was also the first year of Ende Gelande, where we led the international bloc that broke through the police lines in a spectacular fashion. The next year, we organised three buses (provided by Theaterstraat) to the second edition of Ende Gelande in Lausitz. In the following years, Klimakamp in the Rhineland would become a source of inspiration and a practical school for our movement-building efforts, and thousands of people would be initiated into mass actions. Like carbon emissions, solidarity knows no borders, and we benefited greatly from the support of our international allies for years to come.

Having mobilised more than 130 people for Lausitz, the first seeds of codeROOD began to sprout. We came together around a shared analysis: that the governments would be unwilling or unable to implement the Paris Agreement, so it would be people-power to push through the necessary measures. After the inaugural action conference in 2016 to establish goals, values and organising principles, the name codeROOD was adopted the following year. Before “climate emergency” became a popular demand, we were eager to sound the alarm loud and wide.

Actions.

Then came the first codeROOD action camp and mass action in June 2017: taking over Amsterdam’s coal harbour for a day with over 300 people, bringing the iconic look of white overalls to the often forgotten, dirtiest corner of the city. With this action we grew in confidence at the frontlines as well as behind the scenes. This action was enough to put “radical climate activists” into the radar of the Dutch State’s counter-terrorism unit — a label we wear with pride.

A year later, we stepped out of our (Randstad) comfort zone and took our solidarity to the most important ‘sacrifice zone’ in the continental Netherlands: the province of Groningen, where the people of Groningen are suffering from decades of earthquake-inducing gas extraction. This involved months of building alliances with local activists and upholding the values of our international movement, building on the local organising work that had been done by others like GroenFront and Milieudefensie.

The result has been the largest civil disobedience action for climate justice at that time. In August 2018, over six hundred people organised into five groups (“fingers”) reached our target, the entrance to the tank park in Farmsum, by foot, train, bus, bike and boat to set up a three-day blockade with 650 people. By disrupting this chokepoint we supported people in Groningen in raising the urgency of their situation and contributed to pressure the government to close the gas field. This was also the first time that the climate movement was met with severe police violence in the Netherlands. By uniting with the rightfully angry people in Groningen we became a threat to the status quo.

This successful camp and mass action also revealed some of our challenges as a collective. The campaign exhausted many core organisers, and we did not have a clear next step for the influx of newcomers. Many of us also had to confront our own predominantly white, urban, middle-class biases. We pursued this difficult but necessary introspection as we supported Kick Out Zwarte Piet actions. Addressing privilege, intersectionality and decolonisation remained an ongoing learning process as we took the movement forward.

We pursued our movement-building efforts with the Bloc for Radical Climate Justice at the historic 2019 Climate March in Amsterdam which brought 40.000 people into the streets. Organised in collaboration with Fossil Free Culture NL and bringing together more than 20 organisations, our bloc called for a more “intersectional, anti-capitalist, disobedient, decolonial and solidary” movement. More recently, the broad-tent protest rebranded itself as March for Climate and Justice to incorporate some of these values.

Escalation.

By 2019, the movement had reached a tipping point: momentum was building around Climate Strikes all over the world, Extinction Rebellion spreading from the UK and the Sunrise Movement in the US. To put it bluntly: we were no longer the only ones in the Netherlands taking disobedient climate action. This prompted us to reflect on our role in this evolving landscape. We asked ourselves how to pass on our experience and analysis to a new generation entering the movement.

As a result, we adopted a steep escalation strategy: rather than targeting infrastructure sites and confronting workers, we would disrupt the fossil fuel industry’s systemic drivers of the climate crisis. This involved directly tackling the shareholder meetings of the major carbon companies. Our goal was to create a confident and positive language on Just Transition. We also aimed to propose an action that is much more accessible, disruptive and attention-grabbing.

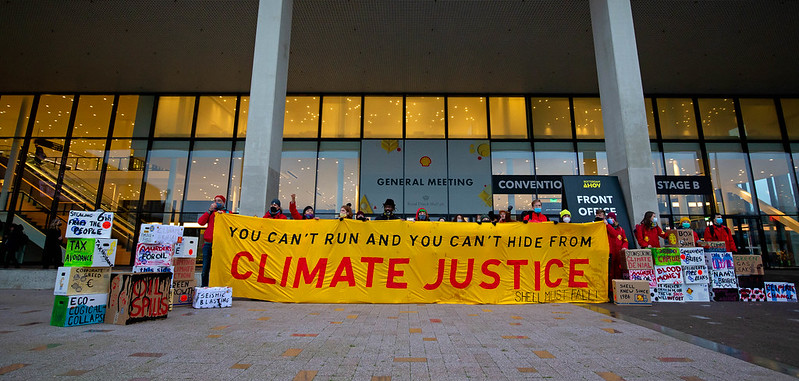

During the Annual General Meeting of Royal Dutch Shell in May 2019, our spokespeople addressed the Board and shareholders with the Shell Must Fall declaration. They professed to block, disrupt and cancel all future Shell AGMs, and called for creating a broad coalition under the Future Beyond Shell banner to work towards a Just Transition. This dual-identity attracted a wide range of partners from NGOs and think-tanks to existing grassroots groups and newest Fridays for Future strikers alike.

Over the next year, we worked tirelessly to keep our promise. By March 2020, we were less than 100 days away from the big moment and we had become the most highly anticipated climate action of the year (according to Andreas Malm). Hundreds of activists across Europe had signed up to take part in the action. We were scrambling to secure funding and accommodation, to arrange action logistics, legal and media support. Our capacity was stretched too thin. We were laser-focused on the action, neglecting our bodies and our relationships.

And then the pandemic hit. Overnight, everything began to unravel: Shell quickly (and conveniently) moved their meeting online, leaving us with no target. Suddenly it became irresponsible to get together to organise, let alone host hundreds of people. As the action was cancelled, many of us lost our shared purpose, and we lost our collective ability to adapt. Some of us showed remarkable resilience to carry on with the campaign further, while others gave up altogether. We were certainly not alone in feeling disoriented, but it affected us particularly deeply.

During the pandemic, we organised several smaller protests targeting Shell. We remembered to organise in a decentralised way to keep the groups small. In 2020 and 2021, we showed up for their AGMs, bringing a cannonball in 2021 and a strong message that the Shell headquarters should be transformed into a Museum for Climate Justice.

We also paid attention to Shell’s crimes in Nigeria, remembering the 25th anniversary of the killing of the Ogoni 9. We put together a toolkit to inspire others to take action against Shell.

Perhaps the biggest lesson is this: history will continue to throw unexpected shocks and crises. We cannot have a master plan that relies on a single day, a single tactic, a single choreography. If we are to become more resilient as movements, we must learn to nurture lasting relations as much as we nurture disruptive actions. We should remember to value invisible care work as much as we celebrate daring gambits. We should aim for emergent strategies rather than fixed outcomes. Our work should be useful whether we are moving towards an eco-social transition or falling into an eco-fascist collapse of the current order.

Aftermath.

While the climate movement had largely lost momentum during the pandemic, there have been a few developments worth noting as we closed this cycle of resistance. In May 2021, a landmark court ruling in the Hague forced Shell to nearly halve its emissions this decade. This unprecedented decision underscored our point: Shell has no future, and must be dismantled by any legal, political or financial means necessary. Taking incremental steps, the government forced Shell and Exxon to shut down the biggest gas field in Europe. The wells in Groningen stopped pumping in October 2023. Yet still to this day many people are still waiting for compensation to repair and strengthen their houses against the continuing earthquakes.

In November of the same year, another major plot twist took place: Shell decided to move its headquarters away from its 130-year-old Dutch motherland and restructure as a wholly British company. They cited “simplification” as their reason, but even the Financial Times acknowledged that climate activism and the Dutch court case in the Netherlands were important factors in the decision. We firmly believe that Shell can run but not hide from Climate Justice; we are delighted to see our comrades in the UK that keep making life hell for Shell.

In the Netherlands, momentum has been rebuilding thanks to the tireless efforts of our comrades at Extinction Rebellion, whose perseverance in repeatedly targeting A12 and demanding the abolition of fossil subsidies has brought about a moment of reckoning for Dutch society as a whole. In addition, strategic partnerships with Greenpeace to shut down private jets at Schiphol have been remarkably effective in reframing the climate debate. There are many entry points for the movement, and the numbers are growing again.

In 2022, a new group emerged in Belgium carrying the name of Code Rouge | Rood. This movement is of a different nature, being a coalition of existing organisations and movements. We nonetheless dare to dream that they were inspired by our namesake, and that they will build upon the experiences and learnings from the former codeROOD.

Some questions remain unanswered: what is the role of mass civil disobedience at this late hour, surrounded by floods, droughts, hurricanes and wildfires, in the midst of food, water and cost of living crises, and facing a transnational alignment of fascist state governments and political leaders? Who will blow up the pipelines? How to become more effective anti-fascists? How can we turn the tide towards justice and peace?

As it always has been, it is up to us, people who resist, rebel and disrupt, to solve these riddles of history.

Invitation.

Have you been involved with CodeROOD? Then we would like to welcome you at our composting event, the 27th of January.

Making and writing history is not an exact science. This is even more true for movement histories/herstories. This text is by no means intended to be a definitive history of codeROOD, but an invitation to reflect together on our common path and divergent perspectives. We hope this conversation starter will encourage you to attend our “Composting codeROOD” event where you can contribute to our oral history recording session as well as strategy discussion on what comes next.

- Saturday 27 January 2024, doors open at 5pm, dinner served at 7pm, party until 11pm

- NieuwLand, Pieter Nieuwlandstraat 93, 1093XN Amsterdam (next to Muiderpoort station)

- free entrance, consumptions and donations by cash or pin

- Sign up here for the event.